Get Healthy!

Staying informed is also a great way to stay healthy. Keep up-to-date with all the latest health news here.

11 Mar

Simple Blood Test May Predict Dementia in Women Up to 25 Years Before Symptoms

New research finds women with high levels of a novel biomarker in their blood are much more likely to develop memory and thinking problems and dementia later in life.

10 Mar

A Daily Multivitamin May Slow Biological Aging, Study Suggests

In a large clinical trial, people taking a daily multivitamin appeared to slow their biological aging by about four months over a two-year period.

09 Mar

Recreational Drugs Linked to Higher Stroke Risk, Major Study Finds

A new study involving more than 100 million people found recreational drugs like marijuana, cocaine and amphetamines significantly raise the risk of stroke – even in younger users.

Study Links State Taxes to COVID Lockdown Decisions

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, states that rely heavily on sales tax revenue were more likely to end stay-at-home orders sooner, a new study finds.

Researchers say the findings hint that financial pressures may have played a role in how long some states kept strict rules in place.

“For this study, we looked a...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

FDA May Allow Some Flavored Vapes Aimed at Adults

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) may allow some flavored e-cigarettes back on the market, but there’s a catch.

They would be marketed to adults, not teens.

Under guidance released Monday, the FDA said it may consider approving vape flavors such as mint, coffee, tea and spices like clove or cinnamon. But it will conti...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

FDA Approves Drug for Rare Brain Disorder, Not Autism

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a generic drug for a very rare brain disorder, but said it should not be considered a treatment for autism.

On Tuesday, the agency cleared leucovorin for people with a genetic condition that prevents enough folate, a form of vitamin B, from reaching the brain.

The FDA est...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Dark Sweet Cherries May Help Slow Aggressive Breast Cancer, Mouse Study Suggests

From cobblers to smoothies, dark sweet cherries show up in plenty of recipes, and scientists say the crimson-colored fruit may contain compounds that could help fight an aggressive type of breast cancer.

A team at Texas A&M University studied natural plant compounds called anthocyanins, which give cherries their deep red color. In lab ...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Multilingualism Might Not Aid Brain Aging, Researcher Argues

A researcher is disputing a recent high-profile study claiming that people who live in multilingual countries show healthier brain aging.

The study, published in Nature Aging last year, found that knowing more than one language reduced odds of brain aging by 54%.

But University of Houston psychology professor Arturo Hernande...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Repealing Motorcycle Helmet Laws Leads to More Severe Crashes, Millions in Added Treatment Costs

Letting folks ride motorcycles without helmets can lead to worse injuries from crashes that are more expensive to treat, a new study says.

Repealing a Michigan law that required motorcycle riders to wear helmets resulted in a 26% average increase in hospital costs per crash patient, researchers recently reported in the Journal of the A...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Physical Therapy Costs Vary Widely In U.S., Study Finds

Physical therapy (PT) is important in helping people heal after surgery, manage chronic pain and recover from injuries.

But PT is likely to take a bigger bite out of your wallet depending on where you live, preventing some from partaking in its benefits, researchers recently reported in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Getting evalua...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Lowering Parents' Stress Can Reduce Risk Of Childhood Obesity

Providing support to stressed-out parents might help their children avoid obesity, a new study says.

Children were more likely to eat healthy and not gain weight if their parents participated in training to help manage stress, researchers reported March 6 in the journal Pediatrics.

“We already knew that stress can be a...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Why Childhood Cavities May Predict Adult Heart Disease

The secret to a healthy heart in your 50s might actually be found in the dental records of your 10-year-old self.

A massive study from the University of Copenhagen found that poor oral health during childhood is a significant predictor of cardiovascular issues later in life.

By tracking more than 568,000 Danish children born between ...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

15-Year Study Shows Sharp Rise in Depression Among U.S. College Students

For nearly two decades, the mental health of American college students has been on a downward slide.

A massive new analysis — to be published April 1 in the Journal of Affective Disorders — found that depression is not only becoming more common but is also hitting certain groups much harder than others.

The...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 11, 2026

- |

- Full Page

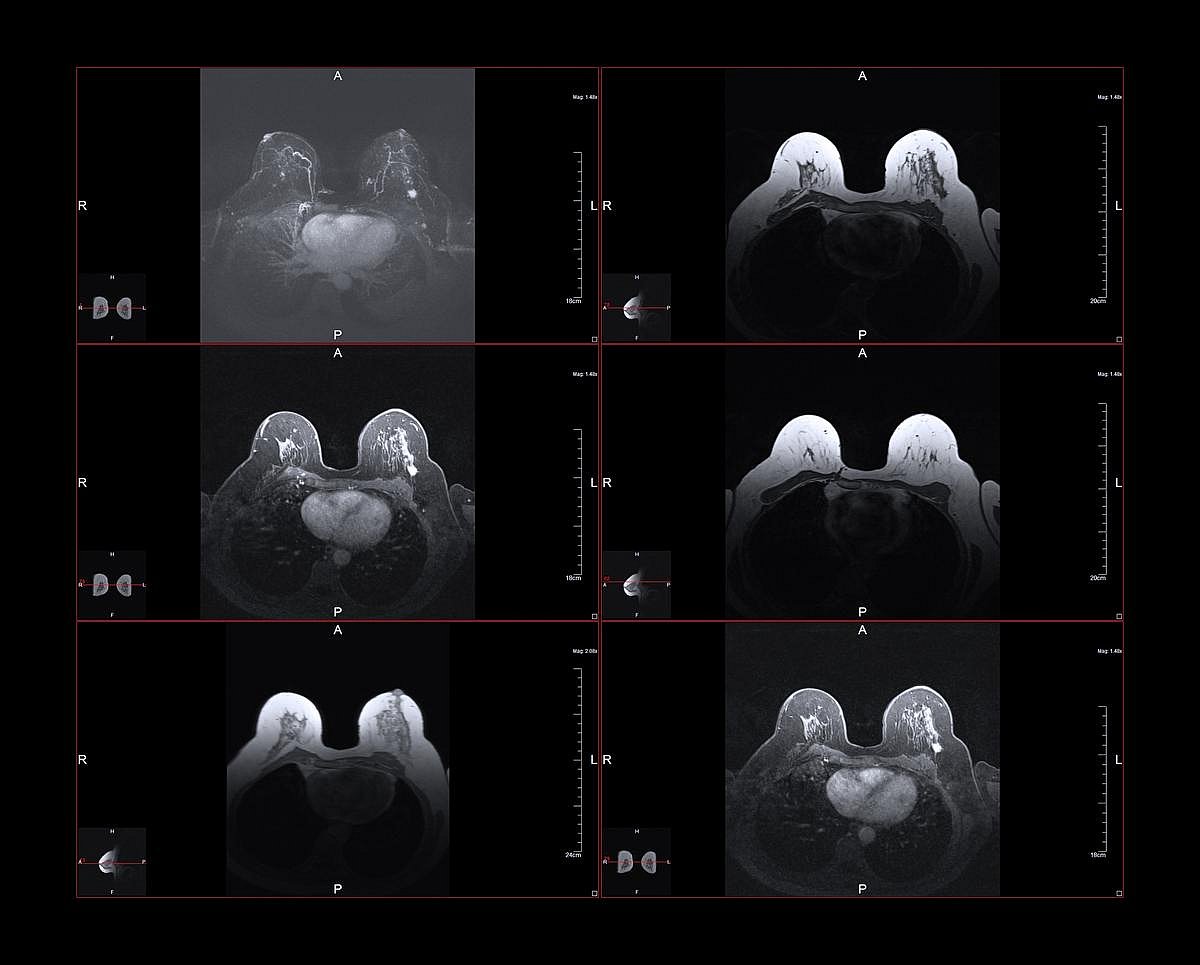

Mammograms May Also Reveal Hidden Heart Disease Risk, Study Finds

A routine mammogram may reveal more than just signs of breast cancer.

New research suggests the scans could also help docs spot early warning signs of heart disease, the leading cause of death in women.

In the study, published March 9 in the European Heart Journal, scientists used artificial intelligence (AI) to examine more...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Going Abroad? CDC Warns Travelers About Polio Risk in Several Countries

Travelers heading overseas may want to check their vaccination records first.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) urges people to make sure their polio vaccines are up to date before traveling internationally.

The warning comes after the virus has been detected in several parts of the world during the past year,...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Raw Oysters and Clams Recalled After Norovirus-Like Illness Outbreak in Washington

Health officials in Washington state have temporarily shut down shellfish harvesting in Drayton Harbor after several folks became sick from eating raw oysters.

The Washington State Department of Health announced the emergency closure for clams, oysters and mussels after illnesses were linked to oysters harvested on Feb. 13 and Feb. 20, 202...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Chile Becomes First Country in the Americas To Eliminate Leprosy

Chile has officially eliminated leprosy, becoming the first country in the Americas and only the second in the world to reach that milestone, health officials announced.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) verified the achievement after confirming that Chile has not recorded a locally transmi...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Students Spend A Third Of Their School Day On Their Smartphone, Study Says

Middle and high school students spend nearly a third of the school day on their smartphones, undermining their education, a new study says.

The students checked their phones dozens of times, often looking at social media or entertainment, researchers reported March 9 in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers also found that frequent...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Daily Multivitamins Slow Aging, Clinical Trial Finds

The health boost from daily multivitamins might actually extend to how quickly a person ages, a new study says.

Researchers found slower “wear and tear” biological aging among seniors after two years on a multivitamin, researchers reported March 9 in the journal Nature Medicine.

Those seniors who began the ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Trump Caused Immediate Decrease in Acetaminophen Rx's For Pregnant Women, Study Finds

The U.S. president’s words are powerful enough to have an immediate impact on medicine, a new study has found.

At a September 2025 White House briefing, President Donald Trump claimed that acetaminophen (Tylenol) could cause autism.

“Don’t take Tylenol. Don’t take it. Fight like hell not to take it,” Tru...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Stress of Pregnancy Complications Might Impact Future Heart Health, Study Says

Women who have pregnancy complications might face a higher risk of heart disease, a new study has concluded.

The stress of these complications increase a woman’s risk of high blood pressure for years after they deliver, researchers reported March 9 in the journal Hypertension.

“For women who were having babies fo...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Approved IV Drug Reduces Lupus Symptoms, Clinical Trial Finds

An already-approved IV drug significantly reduces the symptoms of lupus, a new clinical trial showed.

More than three-quarters of lupus patients taking obinutuzumab (Gazvya) had a significant improvement in their symptoms after a year on the drug, researchers reported March 6 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Nearly Half of U.S. Kids Lack Adequate Sleep, Survey Shows

Nearly half of all U.S. children aren’t getting the sleep they need, a new National Sleep Foundation survey reports.

About 44% of children do not consistently get the recommended amount of sleep for their age, according to results from the 2026 Sleep in America Poll.

What’s more, parents often underestimate how much sleep...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 10, 2026

- |

- Full Page

.jpg?w=1920&h=1080&mode=crop&crop=focalpoint)