Get Healthy!

Staying informed is also a great way to stay healthy. Keep up-to-date with all the latest health news here.

06 Mar

Chronic Back Pain Can Make Everyday Sounds Hard to Tolerate

A new study finds patients with chronic back pain experience ordinary noise as more intense and unpleasant.

06 Mar

How Allergy Season Affects Students’ Academic Performance

In a new study, high schoolers exposed to high pollen counts during exam season scored lower, especially in math and science.

04 Mar

Younger Adults Face Growing Threat From Colon and Rectal Cancer

A new report from the American Cancer Society finds colorectal cancer is increasingly affecting younger adults. The analysis also highlights rising rectal cancer cases, late diagnoses in people under 50, and ongoing gaps in screening.

Some Patients Keep Weight off With Fewer GLP-1 Injections, Study Finds

Some patients taking popular GLP-1 weight loss drugs may be able to keep the weight off while taking injections less often, according to a small new study.

The idea began when Dr. Mitch Biermann, an obesity and internal medicine specialist at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, started noticing a pattern among his patients.

Several told him...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Sixth Measles Case Confirmed in New Mexico Jail

Health officials in New Mexico say the state now has six confirmed measles cases, including a newly reported case linked to a jail in Las Cruces.

The latest case involves a federal detainee at the Doña Ana County Detention Center, according to the New Mexico Department of Health.

Officials say people who visited the U.S. Distr...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

RFK Jr. Urges Medical Schools To Add More Nutrition Training

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced a new effort Thursday aimed at getting medical schools to spend more time teaching students about nutrition.

Federal officials say 53 medical schools have already agreed to take part in the voluntary initiative.

The program has asked schools to review their current nutrition train...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

45,000 Halo Magic Sleepsuits For Babies Recalled Over Choking Risk

About 45,000 HALO Magic Sleepsuits for infants are being recalled after reports that part of the zipper can come loose and create a choking hazard.

The recall was announced March 5 by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and affects certain sleepsuits sold in the United States, according to safety officials.

The problem involv...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Racial Disparities Persist In Lung Cancer Treatment, Study Finds

Black lung cancer patients are less likely to receive surgery or radiation therapy aimed at curing their cancer compared to white patients, a new study says.

This gap has persisted with minimal improvement since the early 1990s, researchers reported March 2 in JAMA Network Open.

“The past 30 years have seen tremendous ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

GLP-1 Weight-Loss Drugs Prove Effective Across Diverse Patient Groups

As the popularity of medications like Ozempic and Trulicity for losing weight continues to soar, folks may wonder: "Will they work for me?"

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health sought to shed light on that question by analyzing results of dozens of studies on the drugs.

The takeaway: GLP-1 receptor ago...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Chronic Pain Can Make Noise Unbearable By Rewiring The Brain, Study Says

Everyday sounds add to the torment of a person with chronic back pain, apparently because pain rewires how the brain responds to noise, a new study says.

People suffering from back pain process sounds differently and more intensely, adding to their agony, researchers recently reported in the Annals of Neurology.

“Our f...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Angry Teens May Age Faster, Study Finds

Your confrontational, angry teenager could wind up growing old before their time, a new study says.

Aggressive behavior as a teenager is linked to faster biological aging by age 30, researchers reported March 5 in the journal Health Psychology.

These angry teens also are more likely to pack on excess weight by that age, rese...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Peanut Allergy Risk Higher If Older Sibs Eat Peanuts, Study Finds

Young kids have a higher risk of peanut allergy if their older brothers or sisters love to eat peanuts, a new study has found.

However, this risk can be headed off by getting younger siblings to eat peanuts themselves, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) in Philadel...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Telemedicine Not Closing the Mental Health Gap in Rural Areas

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, many health experts envisioned telemedicine as a "magic wand" that would bring mental health care to the most remote corners of the country.

But a new study suggests that while the technology is now common, the digital divide for rural Americans remains as wide as ever.

Researchers an...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Rising Tree Pollen Counts Signal Start of Allergy Season

If you live in parts of the West and South, you may already be reaching for your allergy meds.

Tree pollen is ramping up in those regions, according to AccuWeather.com, which issued its 2026 pollen forecast on Wednesday.

"Temperature, rainfall, wind and springtime frosts all influence how much pollen ends up in the air," it sai...

- Carole Tanzer Miller HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Finding the Right Supportive Footwear for Pain Relief is Key, Say Podiatrists

If you suffer from persistent foot or lower body discomfort, the solution might be found in your closet rather than your medicine cabinet.

Podiatrists emphasize that the right footwear does more than just cushion your steps: It serves as a medical tool that can improve your overall physical health.

While many people associate o...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Fewer Mothers Died During Pregnancy or After Birth in 2024

Deaths linked to pregnancy and childbirth fell slightly in the United States in 2024, new data show. Early data suggests the decrease may have continued into 2025.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 649 women died during pregnancy or within weeks after giving birth in 2024. That’s lower than the 6...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Trader Joe’s Pulls Frozen Meals Tied to 37 Million-Pound Nationwide Recall

Trader Joe’s is recalling several frozen food items after reports that they may contain small pieces of glass.

The grocery chain said four frozen products could be affected and asked customers not to eat them.

The recall is linked to a much larger recall involving nearly 37 million pounds of food made by Ajinomoto Foods, ...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

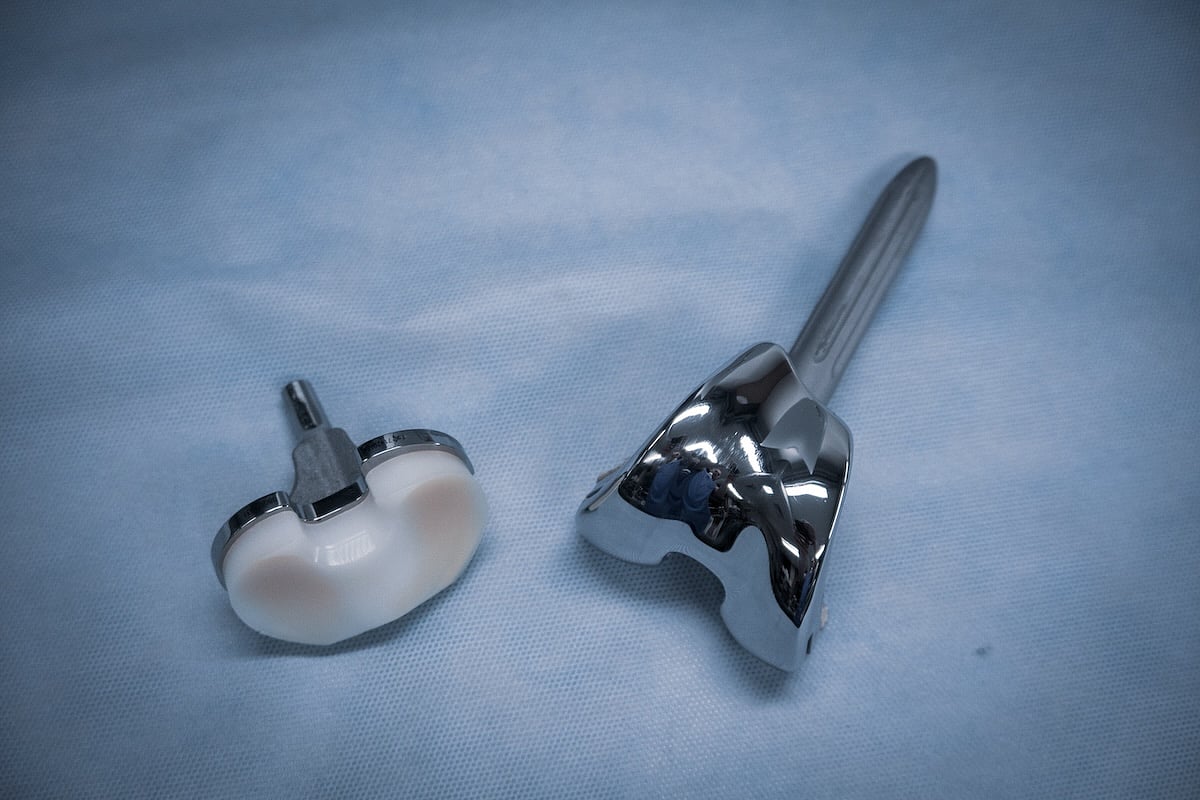

Testosterone Therapy Could Mean Trouble For Knee Replacement Patients, Study Warns

Testosterone therapy is booming in the U.S., but it might bring higher risks for people undergoing knee replacement surgery, a new study says.

Patients who took testosterone within a year of their surgery had a higher risk of infection, blood clots, kidney damage, pneumonia and knee instability after the procedure, researchers reported thi...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Dentists Can Help Detect Undiagnosed Diabetes, Study Argues

Dentists might be able to help detect diabetes among their patients with a simple chairside test, a new study says.

A finger-prick blood test taken during dental exams found that more than 1 of 3 dental patients had elevated blood sugar levels consistent with either diabetes or prediabetes, researchers will report in the April issue of the...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Ultra-Processed Foods Linked To Emotional, Behavioral Problems In Preschoolers

Ultra-processed foods can have an impact on a young child’s emotional and behavioral development, a new study says.

Kids who eat more ultra-processed foods have a higher risk of problems like anxiety, fearfulness, aggression or hyperactivity, researchers reported March 3 in JAMA Network Open.

In fact, for every 10% inc...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Study Links Rising Cannabis Use to Poor Mental Health

For many, cannabis is a go-to for stress relief, but a large Canadian study suggests that for many, that fix may be closely tied to a worsening mental health crisis.

Researchers have found that as cannabis use becomes more common and weed more potent, the link between the drug and serious mood disorders is intensifying.

The study &md...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Fitness Trackers Might Help Predict Multiple Sclerosis Progression

Wrist-worn fitness tracking devices might be able to predict whether a person with multiple sclerosis is more likely to have worsening disability, a new study says.

Data from fitness trackers showed not only who was at higher risk of disease progression, but whose brains might be in danger of deterioration, researchers reported March 4 in ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Half of Americans Unaware of At-Home Colon Cancer Screening Options

Colon cancer is now the deadliest cancer for adults under 50, yet it remains one of the most preventable since polyps detected and removed during screening can’t turn into cancer later.

But a new nationwide survey commissioned by the Colorectal Cancer Alliance reveals a troubling reason why colon cancer death rates are on the rise: M...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 5, 2026

- |

- Full Page

.jpeg?w=1920&h=1080&mode=crop&crop=focalpoint)