Get Healthy!

- Dennis Thompson

- Posted December 15, 2022

Americans' Odds for Parkinson's May Be Higher Than Thought

Parkinson's disease is a much bigger problem than previously thought, particularly for aging Americans, a new study finds.

There are about 50% more new cases of the degenerative disorder diagnosed each year in North America than currently estimated, researchers concluded after an extensive data review.

"We used to say 60,000 people a year were getting diagnosed, but really it's 90,000 people a year are getting diagnosed with Parkinson's disease," said co-researcher James Beck, chief scientific officer at the Parkinson's Foundation.

The results highlight that increasing age is a primary risk factor for Parkinson's, Beck said. With an aging population, more cases of Parkinson's are being diagnosed.

The new estimates align with a 2018 study which projected that Parkinson's cases are expected to double within two decades, rising to more than 12 million worldwide by 2040, said Dr. Xin Xin Yu, a neurologist with the Cleveland Clinic's Center for Neuro-Restoration.

"I feel that this study is really a call to action," Yu said of the new report. "How do we care for an aging population who is living longer? How do we advocate for better care for this aging population at risk for Parkinson's disease?"

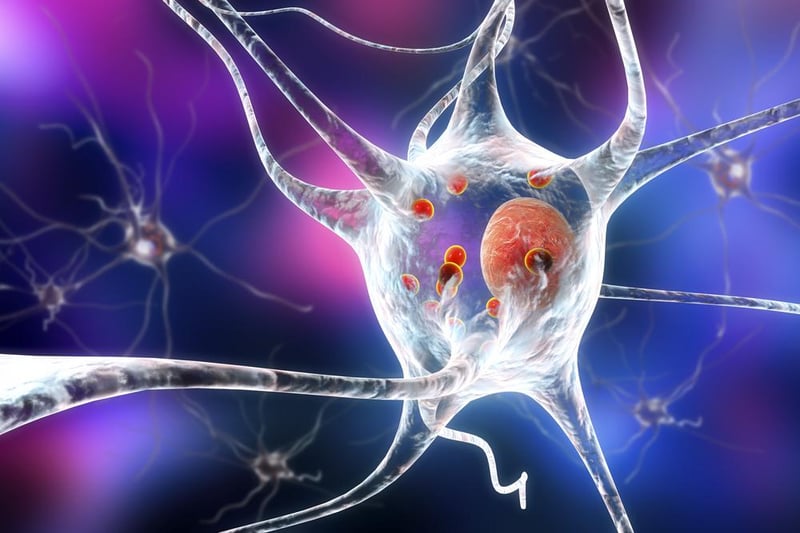

Parkinson's disease affects a region of the brain called the substantia nigra, which produces an important chemical called dopamine. Dopamine transmits messages between nerves that control muscle movements, and also plays a role in the brain's pleasure and reward centers.

It's normal for cells in the substantia nigra to die as you age, but for some the loss happens rapidly, according to Johns Hopkins. When more than 50% of the cells are gone, a person's dopamine production falters to the point that Parkinson's symptoms start to occur.

Primary symptoms of Parkinson's involve tremors, slowness of movement, limb stiffness and problems with gait or balance, according to the Parkinson's Foundation.

Up to now, estimates of Parkinson's cases have been less than definitive because studies tended to look at specific regions and smaller groups of patients, Beck said.

"Here we're utilizing a wide array of data sets, pooling them together to get that better estimate," Beck said. "By pooling data sets from different geographic areas of the United States and Canada, we're able to get a sense of how many people a year are being diagnosed."

The numbers showed that the risk of Parkinson's dramatically increases with age, with men more likely to develop the disease than women.

The data also revealed specific regions in which more cases are diagnosed, which jibes with research linking Parkinson's to pollution, pesticides and other environmental factors, Beck and Yu said.

"It's something that hasn't really been demonstrated in an authoritative way in people, that these exposures are causing Parkinson's disease," Beck said. "We're right now at the cusp of going from epidemiology, which shows us the correlation, to figuring out causation."

Parkinson's rates are higher in the "Rust Belt" states of the northeastern and Midwestern United States, as well as in the central valley of Southern California, southeastern Texas, central Pennsylvania and Florida, the study showed.

"It's hard to pinpoint one single environmental factor, but there has been research looking into the impact of pesticides and byproducts of industrialization and different chemicals" on Parkinson's risk, Yu said. "There needs to be more research looking into why there are certain geographic areas where we're seeing higher incidence."

More than anything, the study provides a new understanding of Parkinson's toll on American society, Beck said.

"Not knowing who actually is living with Parkinson's disease, how many people are getting diagnosed a year, really makes it difficult to talk to policymakers and advocates for why there needs to be increased funding for Parkinson's disease research," Beck said.

Beck noted that about a million people in the United States have Parkinson's, compared to 5 million people living with Alzheimer's disease.

"There's a fivefold difference between the diseases, but it's closer to a 10-fold difference in how much is being invested in Alzheimer's versus Parkinson's," Beck said. "We're trying to make the case that Parkinson's should be on a proportional footing as Alzheimer's. If we could at least get to parity on a proportional basis for Parkinson's funding, that would be tremendous."

The new study was published Dec. 15 in the journal npj Parkinson's Disease.

More information:

Find out more about Parkinson's at the Parkinson's Foundation.

SOURCES: James Beck, PhD, chief scientific officer, Parkinson's Foundation; Xin Xin Yu, MD, neurologist, Cleveland Clinic's Center for Neuro-Restoration; npj Parkinson's Disease, Dec. 15, 2022